At the end of us

we drop our manners,

don’t even stop for a proper

goodbye. Instead, we wander off

to all the places we would rather

be. We scale down to skeletons,

bare-boned, unhearted. The bodies

we were to each other lie rumpled

in a corner. We no longer need

them. Don’t know them.

They look like the yesterday

that is just about start.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

from Café Crazy

Charley explains baseball to me

and how it’s about history,

game six and Gehrig and so many

stats. I tell Charley that history

hasn’t been kind to him and me,

and I remind him about the night

he hooked up with the ice cream girl,

and how I forgave him because booze

was already the other woman. Of course,

I say this only in my head. Charley stopped

listening long ago. And I think about leaving again,

and again, I think how easy life could be, how

just like the clean smack of the bat or a baseball

birding through the sky. And that’s when Charley

tells me how he could’ve gone pro. Star catcher

in the pee-wee league, and later scouted

in high school, but the damn drink hooked him

early, easy fish. He takes a deep breath

and says he’ll tell me more later, and

I settle back in for the evening, looking

at the boy that lives in Charley’s face.

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

from Café Crazy

Roses

Charley buys me three and even

names them – Agnes, Brunhilde, and Pearl.

I tell him flowers don’t live long enough

for names, and he just winks and says,

like love. Maybe he’s thinking our love

went nameless long ago, and these flowers

are marking its grave. No matter.

I like the aroma, the red, red fullness.

I put them in a vase, and they spread

apart, look like the top of the asterisk

I might someday put next to Charley’s

name. Yeah, it would say, he was

technically my lover, but really that

was me being broken. Later that week,

when the roses droop into the asterisk’s

bottom half, Charley says I depressed

them, especially Agnes, and couldn’t I

please be happy for once? I promise

to try harder, and when the girls finally die,

turn into rosecrumble scattered on the floor.

I sweep it up quick so no one has to see

the mess. Like love, I want to tell Charley,

almost exactly like love.

unner da bridge

1080 x 1349 pixels

©2017

lace lights

1080 x 1080 pixels

©2017

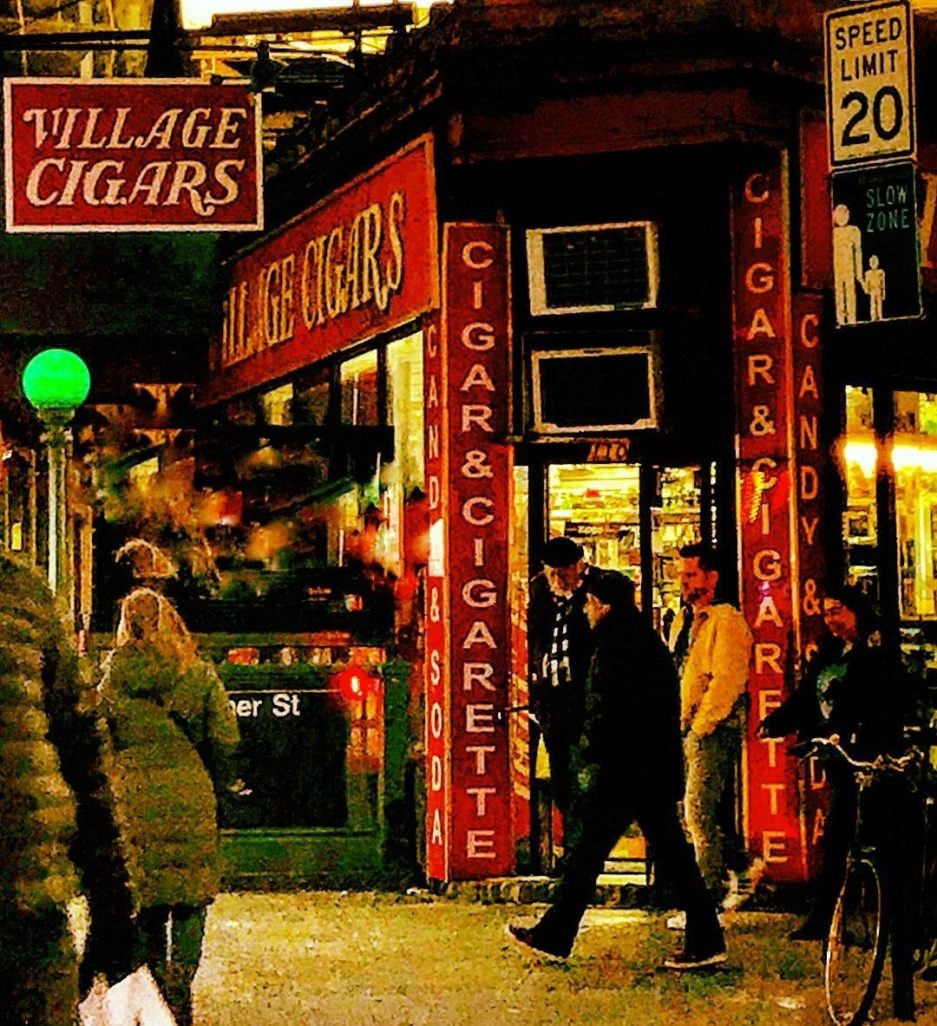

smokes

1080 x 1183

©2017

Alarm clock

and how it’s about to ring. About to get this thing started. This thing called the workday. A part of this thing called a marriage.

So it rings, and the wife part of this thing called a marriage plops together a plate of food for the husband part. They chew and swallow in the same order. Eggs, then toast, then coffee gulp.

Then it’s the dress up part. Ties and pantyhose and who are you wearing cologne for?

Then it’s the out the door part. Kisses and mumbles and what will you do when I’m not watching?

Inside, and left behind, the kitchen fills with all their anger. It’s important not to take it out into the world. It’s important to leave it in the coffee maker, in the copper pots. It’s important not to take it to the jobs they hate more than the marriage. Important not to whisper it into the ears of their lovers. Important not to use it to drown out the alarm that will ring at some point, telling them it’s time to go home.

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

July

100 degrees, and when you ask Reynaldo what happened to his wife, he starts to zipper shut. You change the subject. “Do you like the Ferris Wheel at the amusement park?” you ask, trying to be light and funny. “They don’t let you on without a partner.”

“I killed her, okay?” Reynaldo says, his face flush behind the five o’clock shadow.

“Well, you must have had a good reason,” you say, determined to salvage the moment.

“No,” he says. “It was a ruthless act. I am almost a little proud.”

You like this about Reynaldo – his lack of melancholy and remorse. So refreshing after the bubble-wrap geeks you are used to.

Later that night, you shimmy over to the amusement park. You intend to keep this thing going and head straight for the Ferris Wheel.”

“Tell me, Reynaldo,” you say, “if I were to fall, would you try to capture me?”

You see the zipper closing again. You may have struck the wrong chord. You move up three spaces in line, and that’s when you see a young woman falling from the top of the Ferris Wheel, her legs in flowered tights forming a victory V.

“That’s how my wife died” Reynaldo says, his hand dancing near the small of your back, the thinnest film of sweat forming there, having nothing to do with July.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

Hour

This is the story of 6:00 a.m. Not the 6:00 a.m. of clinking milk bottles or sun climbing the sky. This is the 6:00 a.m. of a house on fire, about to go up in smoke. You just wait.

See, this is the story of a 6:00 a.m. where you look over and love is lying next to you a stinky, rotten corpse.

The kind of 6:00 a.m. where you gotta change your address. Again.

That’ll make three times this year. Rudy always finds me. I gotta stop dropping crumbs.

It’s 6:03. I hate digital time. It just numbers your whole life away.

Not like back in Minnesota where mornings are wrapped in blankets of fresh snow. Back then, my clock had a face. I had a face.

These days, Rudy beats up my face. Welts it with big, fisty blows. I got a dime store full of makeup.

I’m grateful for the way booze chloroforms Rudy into a stupor. He’ll stay like this, but not forever. I gotta move. I gotta move slow and unnoticed as time.

I need two things. Katie and my ice skates. Katie’s my three-year-old. It’s cause of her I always leave. Rudy’s been gettin’ at her again. Oh yeah, I know. And he knows I know.

Problem is this. I need my ice skates. Back there in Minnesota, I was training for the Olympics. Spent hours each day at the rink. Trained and trained and along comes Rudy. Good-looking and such. You know. I know you know.

My skates are in the attic. Big old, musty room full of ghosts and all things banished from my pre-Rudy life. My skates were the first thing he got rid of.

Problem is it’s 6:30. Half hour before the digital begins blip-blipping it’s alarm, and Rudy fogs his way back to the surface.

I got Katie dressed and propped in a chair in the living room. She’s an angel. My half of is her winning. Thank God.

Up in the attic, I find my skates by feel. Only dark, morning light and that ain’t much. That’s okay. I’m know them anywhere.

Rudy stands in the doorway with a candle. He’s still blurred over by boozy sleep, but he looms like a monster.

“Maybe this will help.” he smirks.

I have no breath left to hold.

“Where’s Katie?” my first furious words.

“Bitch,” he says, “You bitch. You’ll never see her again.”

The candle is a missile flying out of Ruby’s hand. It misses me and starts a crown of fire. Tongues of white heat licking up the past.

From the soul of the living room, I hear Katie. She is waiting, just waiting. I work a chair against the attic door, run downstairs, and scoop Katie into my arms. I look back once, only once. My non-digital watch says 7:00 a.m. I have made it out alive.

I start up the Honda and aim myself towards the rest of my life. Meanwhile, in the upstairs window, Rudy goes out like a flame.

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

INTERVIEW WITH FRANCINE WITTE [most questions were conceived by the poet, what she wanted to talk about in the context of her work]

1. Do you have a particular subject you like to write about?

I like to write about love relationships, family memories, and the natural world.

2. What is the role of truth in your poems?

I try to make everything sound like the truth even though most of it never happened that way. I attempt this through throwing in enough real or detail, but the overall story is probably made up. In my book, Café Crazy, I have a running story about a person named Charley. People always ask me who he is. I tell them he’s no one in particular, but lots of pieces of people I’ve known. I don’t think people believe me.

3. Since you write both poetry and flash fiction, how do you know which form to use?

I usually decide which genre I’m going to write in. I’ll sit down and say, okay, I’m going to write a flash. I use a lot of poetic language in my flashes, but the main thing is that there is a story. A poem might or might not have a story, but a flash has to.

My process in writing flash is not that different from writing poetry. The way I approach language is always the same. I want to avoid clichés and tired phrases. I want to say something in a way that’s never been said before. That’s when I know it’s working. But there are a few differences. In poetry, you have to decide on form. Is it going to be written in long lines, short lines, couplets? The form is an important element of a poem. Couplets can undercut the seriousness of a poem, allowing too much air in. Similarly, a poem might need the air of couplets or the breeziness of very short lines. And you have to think about line breaks. A line break or a stanza break is another important moment. You don’t worry about this in prose.

Prose has its own concerns. What point of view do you use? Dialogue or no? If dialogue, do you use italics or quotation marks? How much description of a character do you need? Of course, flash is so compact that you just need a word or two to describe a character. I love compression in writing. That’s why I can’t write a novel.

4. How do other poets influence your writing?

I am very aware of voice in other people’s writing. I like to see what forms poets use. If I’m in a couplet-y mood, I might read a lot of couplet poems, just to see how they move. Also, I’m very impressed by how a poet uses language. Those things really make me think about my own voice and use of language.

5. Do you have particular journals you like to read? Why?

I like Rattle, the poems are fun and profound. I like the Southeast Review, Cloudbank, Barbaric Yawp, and South Florida Poetry Journal, among others. I like journals that publish the kinds of poems I like to write.

6. When did you start writing poetry?

I started writing when I was thirteen. Rhymes just came to me, and I liked writing them. My parents were so encouraging. I took a really long break from writing until my late twenties when I went back to college and took creative writing classes. My very first teacher was Julia Alvarez, who was great and taught me all about craft. I just kept writing and started getting published. I soon discovered poetry workshops, writing groups, and poetry readings. Now, this is a big part of my life.

7. What makes a poem good?

A good poem is both easy to understand but uses language to take the reader to another level beyond the words on the page. A good poem says what you can’t say in any other words but the words that are there, and yet your gut knows what’s being said; your inner ear hears the unspoken words.

8. How do you know when a poem is “working”

A poem that is working creates magic. This applies to poems I’m reading and writing. If a poem doesn’t go beyond the words on the page, if it doesn’t create another level of experience–it hasn’t created magic. A poem may succeed on a basic craft level. It might use metaphor or imagery correctly. That’s a good start.

9. What is the importance of going to poetry readings?

There are two types of readings. One you attend to hear a poet whom you admire. You might want to hear how their poems are presented, to see how a more accomplished poet reads and to hear their work, or simply to enjoy it. But in terms of the advantage to you as a poet, it’s the same as tennis; you only get better if you play with someone at a higher level. The other type of reading is the open mic. Open mic readings are important, so that you get reaction to your own work and develop your reading style–and to see what your peers are doing. I think it’s an important component to your life as a writer.

10. How did you feel having your book Café Crazy published?

It’s nothing less than a dream come true. I had had several chapbooks (both in poetry and flash fiction) published and was thrilled with that, but having the whole collection published was really another level of happiness. I am now trying to have the same thing happen with my flash fiction.

11. What are you working on now?

Right now, I’m working a bit more on flash fiction, but I’m still writing poetry. I really enjoy both. I’m looking to get my full-length collection of flash stories published.

12. How does reviewing influence your own writing? (You are a reviewer for South Florida Poetry Review and others on occasion)

Writing reviews allows me to analyze very closely how a collection is put together. What is the main message this collection is trying to communicate? What is the through line? Very often, when I read a book of poetry or flash, for that matter, I jump around, reading whatever appeals to me in no particular order. When I write a review, I read it front to back. I try to find what holds the poems together. Why are they in this order?, etc. I reviewed one book in which the poet kept returning to a theme, rather than grouping the poems together. I tried this technique in Café Crazy with the Charley poems, and it seemed to work better.

13. Is Facebook a good thing or a bad thing for writers?

I love Facebook. It’s given me opportunities I never would have otherwise had. I have connected with writers all over the country this way. I post my poems and people read them and comment on them. When I have a poem in a print journal, it’s very exciting, of course, but a lot of people don’t see it. If I take a photo of the poem and post it, now people see it. It also makes others aware of the journal.

14. Who are your favorite poets?

My favorite poets are George Wallace and Dorianne Laux.

15. Can you talk a little bit about your process of writing poetry and flash fiction? Is the process different for each genre or the same?

My process for writing both forms is pretty much the same. I write a half hour a day. No more. With short forms you can do this. I try to produce one new thing a day. Now, this is not to say that I come up with a good, publishable thing every day. But it’s a goal. If I work on something for more than three days, I know it isn’t working, and I might either abandon it or come back to it later. This is why I don’t write longer work. I like to keep moving. When I revise, I like to just cut a line or change a word. I don’t want to go back and look at Chapter 1 to see what I’ve missed.

I’m very receptive to prompts. I like to look at a photo or take a few random words and see what happens. I have developed a pretty good internal editor that tells me when something isn’t working. Whenever I try to slip something by, it keeps bumping around in the poem. It just look right.

16. What is the subject of your photography and why?

I walk around with my i-phone and take pictures of what I see that I want the world to see. I take photos mostly when I’m walking around Manhattan, but have gotten very interesting shots in Brooklyn and on Long Island. I am very attracted to the textures of things, the roughness of brick, the way light eats up a street. I love how trees and branches overlap and squiggle. I love the combination of trees and buildings. And I love the colors of things.

17. 14. How did you hear about Diaphanous?

I believe I saw it listed on Facebook, probably a call for submissions. I submitted, and I’m certainly glad that I did!

Francine Witte – Poets & Writers

Francine Witte is the author of the poetry chapbooks Only, Not Only (Finishing Line Press, 2012) and First Rain (Pecan Grove Press, 2009), winner of the Pecan Grove Press competition, and the flash fiction chapbooks Cold June (Ropewalk Press), selected by Robert Olen Butler as the winner of the 2010 Thomas A. Wilhelmus Award, and The Wind Twirls Everything (MuscleHead Press). Her latest poetry chapbook, Not All Fires Burn the Same, won the 2016 Slipstream chapbook contest. Her poem “”My Dead Florida Mother Meets Gandhi” is the first prize winner of the 2015 Slippery Elm poetry award. Her full-length poetry collection, Cafe Crazy was published earlier this year by Kelsay Books. She has been nominated seven times for a Pushcart Prize in Poetry and once for Fiction. Her photographs have been published in South Florida Poetry Journal, Anti-Heroin Chic, Sourland Mountain Review, and other journals. She is an associate editor and staff poetry reviewer for South Florida Poetry Journal. She edits the weekly flash fiction column FLASH BOULEVARD on the Facebook blog, Poetrybay. https://www.facebook.com/poetrybay.1152611418123138/ A former English teacher, Francine lives in New York.

Francine Witte Author Photo

©2017