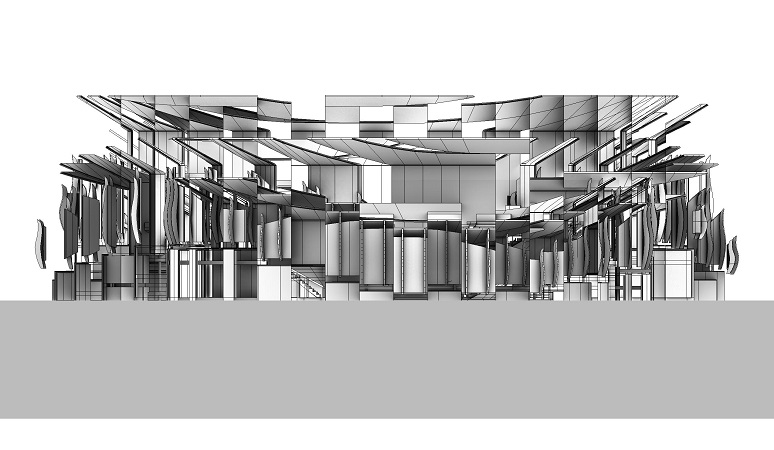

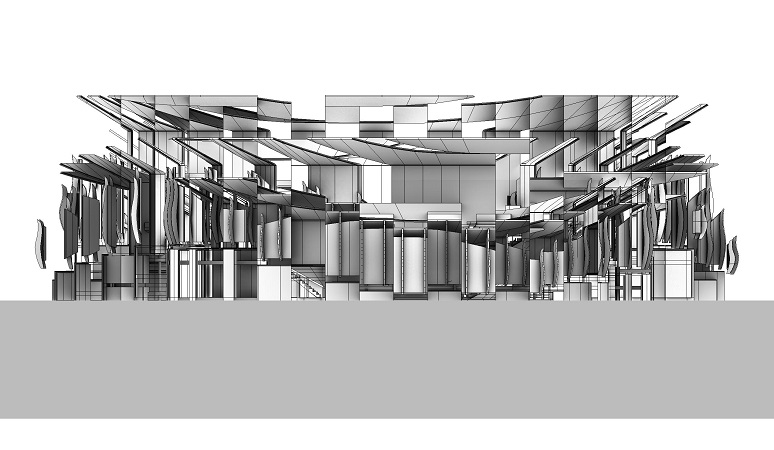

Elevation | North

Digital

8.5” x 5”

©2019

Cutting-edge Architecture and Critical Social Relevance—brief introduction [Krysia Jopek, January 2021]

I’m privileged to feature young architect Kristen Anderson’s vital architectural project in diaphanous micro‘s first issue of 2021. Please enjoy her professional architectural designs that propose a highly complex and artistic way to utilize abandoned buildings to create a place of community for those displaced by poverty. Her innovative designs incorporate contemporary architectural theory and practice to envision a feasible, beautiful structure and site where a displaced community can thrive in the natural environment that is incorporated and honored.

RE-CONSTRUCTIVISM IN THE ABANDONED FIELD: The creation of a new architecture through the process of demolishing and repurposing abandoned structures

ARTIST/ARCHITECT STATEMENT:

Re-constructivism in the Abandoned Field is a conceptual project that is concerned with the development of a new architecture that demolishes and repurposes abandoned structures left behind by temporary enclaves. Abandoned sites are not always a result of the temporary enclave condition; however, many large fleeting events leave behind architectural and structural ruins. By using the remaining residents of Vila Autodromo as a test community, this project expects a successful method of repurposing a site that will attract other people with the drive for a similar lifestyle. The strategic process utilizing a single crane derived from the grid analysis of the past site—creates a clear organizational strategy for how the other abandoned arenas could be manipulated at a later point in time. With the successful implementation of this strategy on the Cariocas Arenas using the local test community, similar success when applied to the rest of the site would be expected. The design strategy for this new hybrid landscape created from built materials can be applied to other abandoned sites as well. Demolition breaks these buildings down to merge with the site once again, while simultaneously repopulating and bringing a revitalized spirit to a once barren site.

The temporary enclave, an enclave that arises when there is a need for a zoned cluster of structure and infrastructure in response to a fleeting event that exists as both a boundary condition and as a porous entity—inspired the development of this project that simultaneously acts as a barrier and as a means of intersection between communities. The intent is to explore the ways in which intersection space derived from a glitched grid can be used to design hybrid structures of architecture and landscape for communal and recreational use. Specifically, this project impacts the past inhabitants Vila Autodromo, a favela that was largely displaced by the construction of the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Barra Olympic Park by Wilkinson Eyre. The concept of the inhabited “wall,” or boundary space, would achieve the porosity necessary to fulfill this unifying task by manipulating the existing site plan until it achieves the properties of a field condition. The hybridization of architecture and landscape into one coherent whole ceases to be a barrier; rather, it becomes something that knits the community together as a self-sustaining entity.

The proposal is designed for communities that need open shared space to grow. Landscape, park, and other agricultural programs will be the catalyst; businesses and homes propagating outward from developed zones is the future goal. The design swerves the principles of landscape urbanism, or urban conditions developed through landscape design, to fit into a new mold: to create an artificial landscape condition within by utilizing elements of architecture that serve as a driving force to repopulate the site.

The 20 families that remain in Vila Autodromo will act as a test community for this architectural catalyst that will eventually attract other past inhabitants back to the site. An analysis of the former site plan of Vila Autodromo led to a strategy for how to manipulate the existing architecture. In this analysis, a seemingly unorganized favela site plan became one of multiple grids overlapping and intersecting each other. The particular moment when multiple paths crossed created a radial language that inspired the placement of a single crane on the site to be used for both dismantling and reassembling the buildings in a systematic process. The successful reuse of the Cariocas Arenas will result in a new architectural system that creates a solution to human displacement and new agricultural space while incorporating the abandoned architecture resulting from the existence of temporary enclaves.

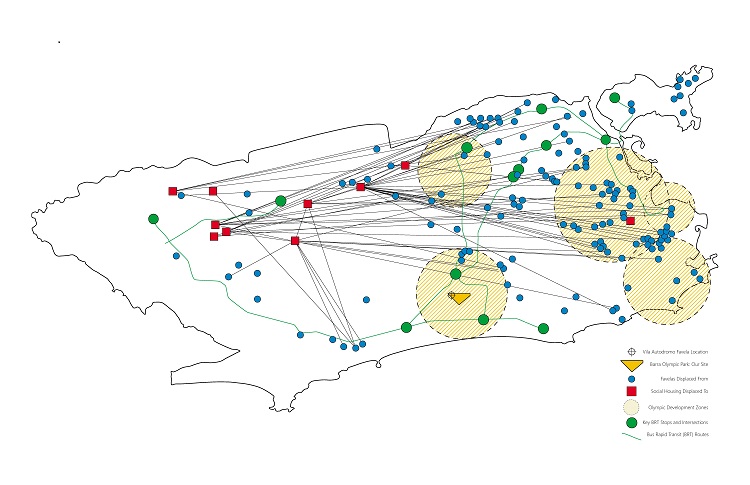

Displacement | Migration of people in Rio de Janeiro

Digital

25.5” x 16.5”

©2019

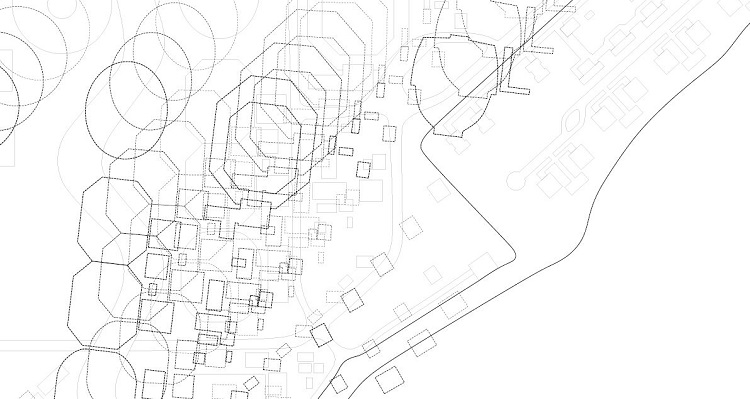

Conceptual Grid | Former site plan of Vila Autodromo

Digital

9” x 6”

©2019

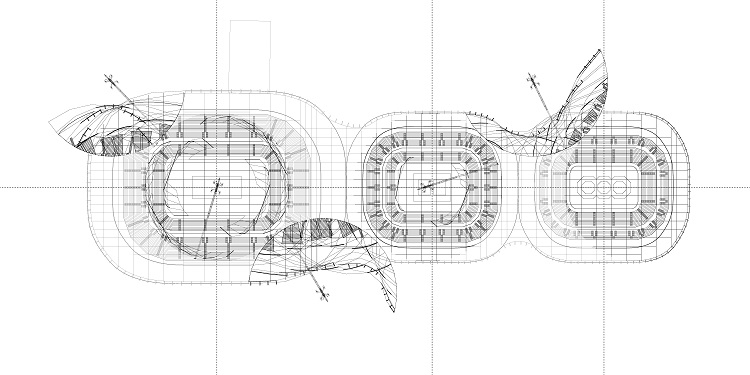

Zoning Intersections | Conceptual field condition manipulating the existing plan of the Barra Olympic Park using sequential rotation operations

Digital

17” x 11”

©2019

Zoning Intersections | Conceptual field condition focus area

Digital

17” x 11”

©2019

Crane Placement | Strategy

Digital

33” x 16.5”

©2019

Design Iteration | Radial Language

Digital

33” x 16.5”

©2019

Program Diagram | Agriculture

Digital

18” x 33.5”

©2019

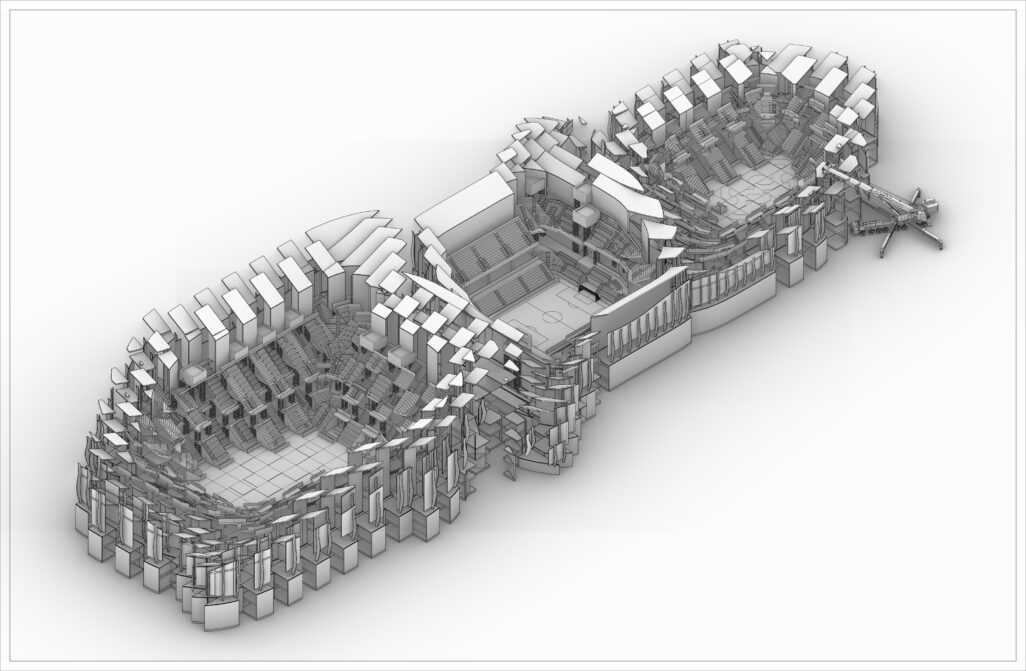

Final Design Proposal | Axonometric

Digital

52” x 34”

©2019

Final Design Proposal | 50% Project Completion

Digital

26.6” x 67”

©2019

Final Design Proposal | 100% Project Completion

Digital

26.5” x 67”

©2019

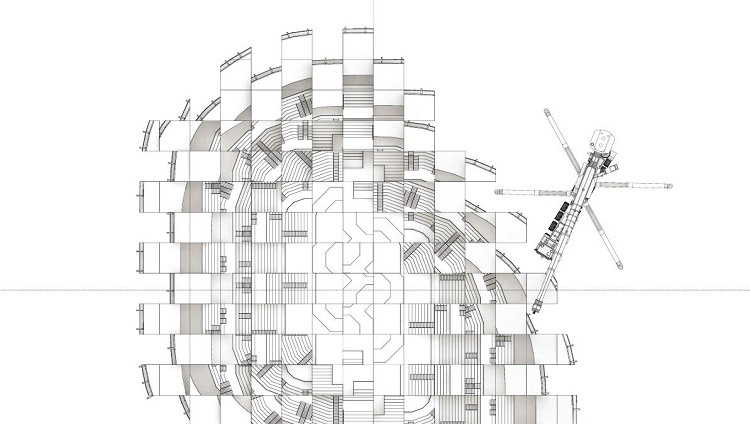

Detail | Cariocas Arena 3 in the process of demolition

Digital

17” x 11”

©2019

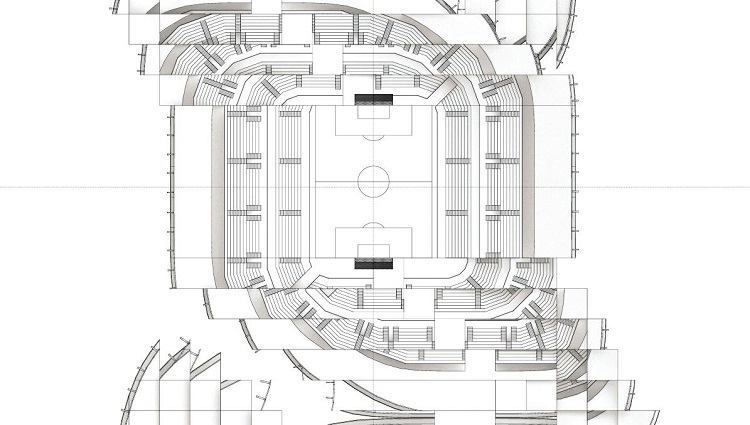

Detail | Formal soccer field to remain in Cariocas Arena 2 despite the demolition of its surroundings

Digital

7” x 11”

©2019

Elevation | East

Digital

8.5” x 2.5”

©2019

Elevation | South

Digital

8.5” x 5”

©2019

Elevation | North

Digital

8.5” x 5”

©2019

Vignette | Cariocas Arena 3 in the process of demolition

Digital

17” x 11”

©2019

Vignette | Recreational soccer field that remains in the location of Cariocas Arena 2 with agricultural terraces located in the periphery of the field

Digital

33” x 33”

©2019

Vignette | Agricultural terraces located in the remains of Cariocas Arena 1

Digital

33” x 33”

©2019

Fragment | Perspectival Section Model

Digital

8.5” x 5”

©2019

Kristen designed RE-CONSTRUCTIVISM IN THE ABANDONED FIELD: The creation of a new architecture through the process of demolishing and repurposing abandoned structures in her fifth year at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s Bachelor of Architecture program.

KRYSIA JOPEK’S INTERVIEW WITH KRISTEN ANDERSON—January 2021

What aspects of architecture excite you the most?

Architecture has always been a passion of mine. I love how a single building can have distinctive impacts on different people. What excites me the most about architecture is that it is an ever-changing, often experimental, form of artistic expression that builds up our surroundings. Like all forms of art, not all architecture will be loved and praised by everyone, but buildings are fundamentally a part of our daily lives. Architecture can be thought of as beautiful, thought-provoking, controversial, lasting, etc. and what means nothing to one person may catch the eye of another. Personally, I enjoy knowing that I can use my creativity to positively impact the world around me.

When did you know that you wanted to be an architect?

When I was a little girl, my mother worked from home as an electrical engineer. She would “bring me to work with her” in her home office where I had a small table set up next to her desk. I would spend hours at this table drawing elaborate scenes of buildings and houses (or so I am told, as I was too little to remember!). Somewhere along the way, my mother asked if I wanted to be an architect. From then on, I told people that I was going to be an architect when I grew up. This is all before I really knew what being an architect meant. As I got older, learned more about architecture and had the opportunity to take drafting courses during high school, I knew that pursuing architecture as a career was the perfect choice for me. Architecture school was nothing like I expected, yet it only helped solidify my lifelong decision to continue on the path of becoming an architect.

Do you think you were born creative?

Like all skills, my abilities to draw, paint, and build needed time and practice in order to become as strong as they are today. I do believe, however, that being creative is an intrinsic part of my personality. From as early as I could hold a crayon, I was doodling and drawing pictures, but creativity is far more than artistic talent alone. Being creative also means being imaginative, and from what I’ve heard of myself as a very young child, I have always been quite original and silly. My creativity and my ability to see the world a little differently has definitely shaped me into the unique, sometimes quirky, person I am today.

Did your childhood surroundings influence / cultivate your proclivity for artistic creation?

My childhood surroundings played a major role in cultivating my artistic ability. My parents have always provided me with support and encouragement in my artistic endeavors. They instilled in me an understanding of and appreciation for the creative process and encouraged me to create beautiful things.

How was your university experience at RPI in the Architecture program?

My RPI School of Architecture experience was amazing! The five-year program continuously challenged me and helped me grow both academically and creatively. Now that I am working in the industry professionally, my appreciation for the strength of instruction I received at RPI has only increased. The encouragement I received from my instructors and peers helped me realize the extent of my abilities and the work I am capable of producing. The mix of technical and artistic education provided throughout the program was a great balance for my skill set. Looking back on the five years, I couldn’t be happier with my decision to attend RPI’s rigorous program—and I am very proud of my degree in Architecture.

Did you have certain professors who mentored you?

My professors definitely had a profound impact on my education. Many of the professors who taught my introductory courses and studios were also my professors in later years as the curriculum became more focused. This allowed my professors to see not only my work ethic and my technical skills, but also how my designs transformed and improved as I advanced through the rigorous program. The personal level of which these mentors got to know me helped guide my work to reflect more of myself. They provided much-appreciated guidance and support as I transitioned from being a student to an employee of an architecture firm.

How were your peers? Was the atmosphere and environment supportive and/or competitive?

My peers in the School of Architecture contributed heavily to my happiness at RPI. I was friendly with so many people in my major, both in my class and in the classes above and below me. The environment was supportive. Because of the many collaborative group projects, lasting bonds and friendships were formed. That’s not to say there wasn’t plenty of healthy competition!

How did your semester studying in Italy impact your creative work?

My semester abroad in Italy changed my life. It was the first time I had ever traveled to Europe, and I immediately fell in love with the new world that this opportunity opened up for me. Studying abroad was always a dream of mine, so I took every moment to learn about and appreciate my surroundings. The architecture in Italy is so different from what I was used to in New York. The semester in Italy studying Architecture helped strengthen my love for ancient and classical architecture. One specific example of the impact the experience had on my architectural eye was mastering the act of “looking up.” The ceilings were works of art in all of the spaces I had the opportunity to explore. So often we forget to design certain parts of a building that might seem insignificant, so the architecture in Italy taught me that when I design I must think about every angle, view, and experience that a person can have in a given space. My semester in Italy also strengthened my sketching abilities and the way I look at the descriptive geometries of a building or space.

Can you describe your process from idea to finish product when designing a project?

My design process usually begins with analyzing the surroundings of a site where the project is to be located, including using grids and projection lines to understand existing spatial relationships. My designs are usually products of this initial study, which leads to sketches, study models, iterations after iteration—until I find a form to work with the program and parameters of the particular project. One aspect of designing a project in RPI’s architecture program is that none of those design projects were ever really “finished.” Even after a final critique, we would be asked, “What are the next steps?” or “Where do you see yourself taking this design further?” Although I have “finished products” in my portfolio, a design project is never truly finished; more can always be done to enhance the design and function of the conceptual work.

What media do you prefer to work in?

I typically use digital media for my architectural drawings, including AutoCAD, Adobe Illustrator, and Photoshop. I particularly enjoy building physical models, which allows me to see a project come to life in 3D.

What are your favorite schools of architecture, time periods, and why?

My favorite time periods in architecture are largely influenced by the time periods I was able to study in-depth at RPI. For example, I have always enjoyed the classic elegance of the Renaissance and the opulence of the Baroque periods that I experienced in Italy. In addition to the Italian architecture I studied while abroad, I have a strong appreciation for Gothic architecture with its monolithic forms, gorgeous stained-glass windows, and complexities with technical innovations such as flying buttresses and vaulted ceilings. I am also a very big fan of Victorian houses. The whimsical design elements create a unique character for each Victorian home, which really speaks to me. I have a dream of owning a beautiful Victorian someday with a wraparound porch and elegant tower.

My own love of architecture grew out of my doctoral studies; my primary areas of interest/focus were twentieth-century American poetry, postmodernism, and post-structural theory (deconstruction, specifically). How much theory did you study at RPI and on your own? What theories most influence your work?

We studied a fair amount of theory and history in our courses at RPI. Deconstructivism played a crucial role in my thesis design by inspiring me to deconstruct, reconstruct, and create a fragmented architecture based on the process of reusing parts of existing architecture. RPI professors did a great job leading us to precedent projects that could influence our work. Rem Koolhaas’ thesis Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture, PV Aureli’s A Field of Walls, and Peter Eisenman’s Rebstockpark were all precedents that greatly influenced my thesis design and concept.

How are you enjoying your first job as a professional architect?

I have really enjoyed the first year and a half as an employee of Hoffmann Architects. We specialize in the rehabilitation of building exteriors; therefore, I work on restoring existing buildings and get to contribute to a critical niche in the architecture field. I enjoy working on older buildings and learning how to create innovative, effective solutions to existing problems that buildings face. My coworkers are great, and the firm has exactly the environment and culture I was hoping for. The firm as a whole is also very supportive towards my ambition of becoming a licensed architect.

What is your typical workday like?

My typical workday starts bright and early with an hour-long commute on the train into Grand Central and a 10-minute walk to my office in Midtown. Typically, I work on project representation through drafting and other necessary paperwork for different phases of a project including writing field reports, editing specifications, and reviewing submittals. On a really exciting day, I partake in site visits where I assist in inspecting the roofs, facades, and plazas of old hotels, churches, and university buildings around New York City. I was a bit nervous the first time I had to climb a scaffold (19 stories high!) but the nerves subsided, and I now look forward to the days when I get to be out in the field. My typical day also consists of lunch breaks in Bryant Park with some coworkers or a good book, and most recently, ice skating at Bryant Park’s Winter Village rink.

What are your hobbies and interests outside of architecture?

Outside of architecture I enjoy many other artistic forms of expression, such as drawing, painting (using mostly watercolor and acrylic), crocheting, and anything that can be made crafty. I enjoy reading and being outside, especially in nice, warm weather. I love trying new things, and right now I’m doing my best learning how to ice skate during my lunch breaks. I have become more adventurous and have started to travel more since my semester abroad. I was supposed to take an exciting trip to see the gorgeous castles and churches of Germany and Austria in September 2020, but then COVID happened. I can’t wait to reschedule that trip!

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE:

An honors scholar and recent graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s Bachelor of Architecture Program, Kristen Anderson is pursuing her lifelong dream of working as architect. She is currently enjoying her first full time position at Hoffmann Architects in New York City, where she works on the rehabilitation of building exteriors. The passion she has for renovating old architecture stems from her interest in classical buildings and her studies in Rome. Throughout her career so far, she has participated in historic preservation work, educational, institutional, and civic architectural projects. Kristen is also an active member in her community with a commitment to service. She dedicates her design and community action experience to many volunteer activities.

LINK TO KRISTEN’S ONLINE PORTFOLIO: https://kristenanderson39.wixsite.com/portfolio

photography by Raina Page

©2018